Recently, Billboard’s Hot Country Songs chart has been topped by an artist that has come as a surprise to some people: Beyoncé. Released in March 2024, Queen Bey’s Cowboy Carter is a country-inspired album, influenced by the country and zydeco music she heard growing up in Houston and attending rodeos with her grandfather. Like her first country song, “Daddy Lessons,” off 2016’s Lemonade, Cowboy Carter has stirred up conversation about Black artists’ place in the predominantly white world of contemporary country music—and their role in the genre’s history. In fact, Black musicians have played an important part in the evolution of the genre at every stage of its development.

Beyoncé on the cover of Cowboy Carter, by Blair Caldwell

“Texas Hold ‘Em,” one of the lead singles from Cowboy Carter, begins with a syncopated banjo lick played by Black multi-instrumentalist Rhiannon Giddens. It is an appropriate intro, as no other instrument more clearly shows the influence Black Americans have had on the genre quite like the banjo. The banjo’s roots are firmly African, with similar lute-like instruments having existed all over western Africa for centuries before enslaved Africans brought them to the Caribbean and the American South as early as the 17th century. By the 19th century, the banjo was well established in American music. Its popularity crossed the color line, with white Americans appropriating the instrument and incorporating it into their own European-rooted musical traditions.

Despite widespread innovation by African Americans throughout the 19th century, as well as widespread use by white Americans, the difficulty in notating banjo techniques has meant that musicians and historians have had little to go on when trying to reconstruct the way the banjo was played in the early 19th century. Banjo sheet music of the time, written in traditional music notation and without modern additions such as tablature, mostly documents melodies. It fails to capture gestural aspects of playing—plucking and strumming styles that can greatly impact the sound of the music played. These techniques would have been transmitted aurally, leaving historians and musicians at a loss when determining when and where specific styles emerged.

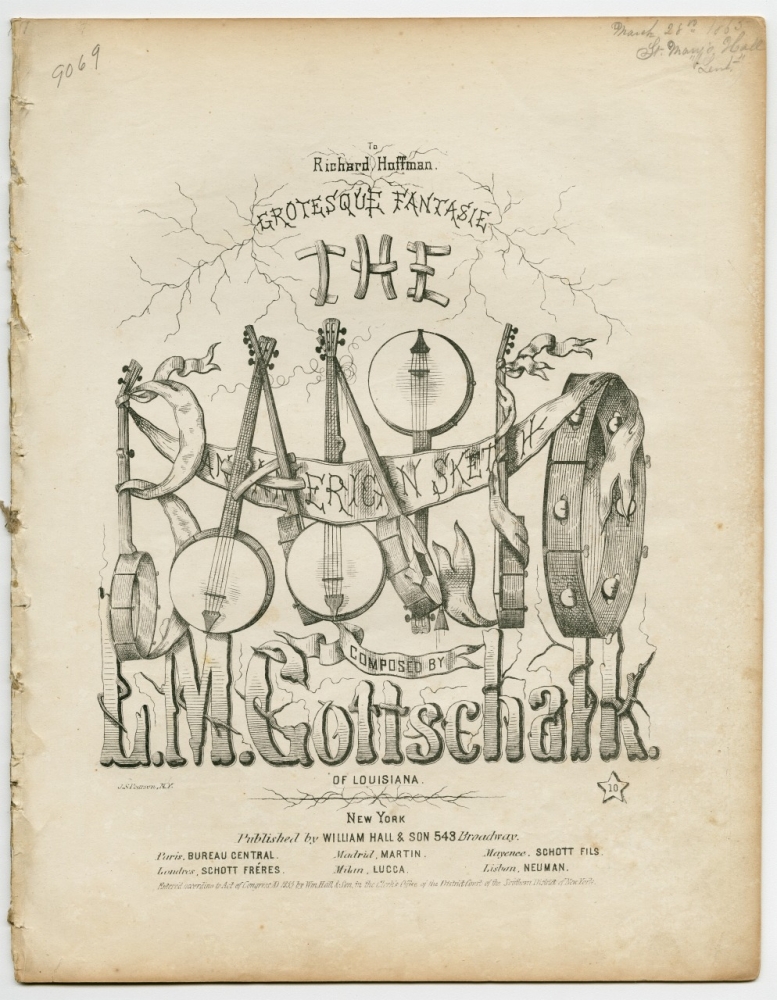

Original score and sheet music for Louis Moreau Gottschalk’s The Banjo (HNOC, 86-917-RL)

White Creole composer Louis Morreau Gottschalk bypassed the limitations in notating banjo music with The Banjo: Grotesque Fantasie, an American Sketch, a piece for the piano that premiered in New Orleans in 1855. This virtuosic piece, like many of his works, incorporates elements of Black music that Gottschalk heard growing up near New Orleans’s Congo Square. The Banjo contains early evidence of African banjo techniques found nowhere else.

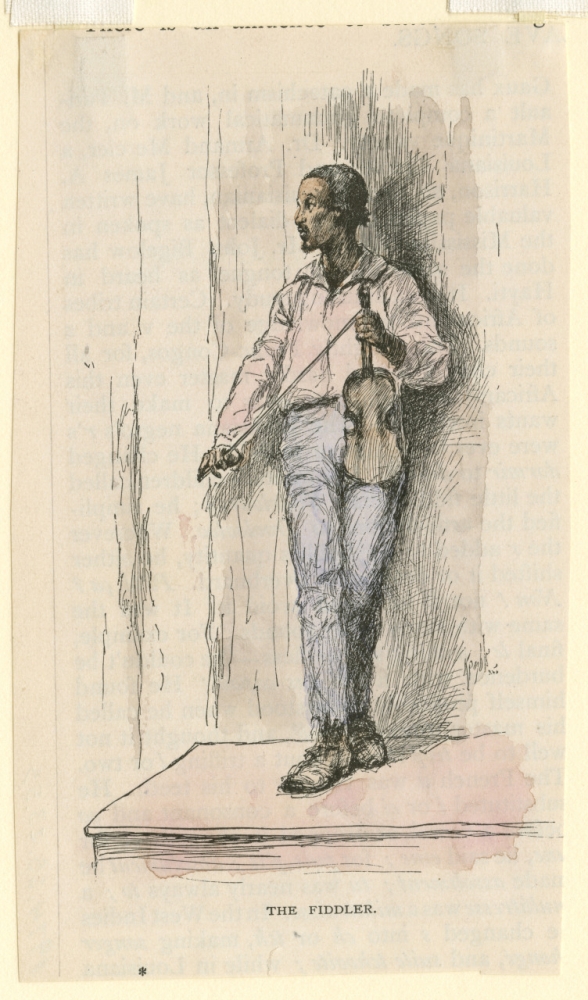

“The Fiddler” by E. W. Kemble, from 1885, depicts a typical musician of New Orleans’s Congo Square in the pre-Civil War period. (HNOC, 1974.25.23.55)

Black contributions to early American folk music extend far beyond the banjo. African Americans have been playing the violin, better known in folk contexts as the fiddle, since the colonial era. Enslaved Africans adopted fiddles in the English colonies by at least the 1690s, and over time they developed unique styles while also mastering those of their European enslavers. Enslaved people were often responsible for providing musical entertainment to white colonists. They mastered the popular forms that would be heard at balls of the era, and in many places they became the primary musicians in the colonies.

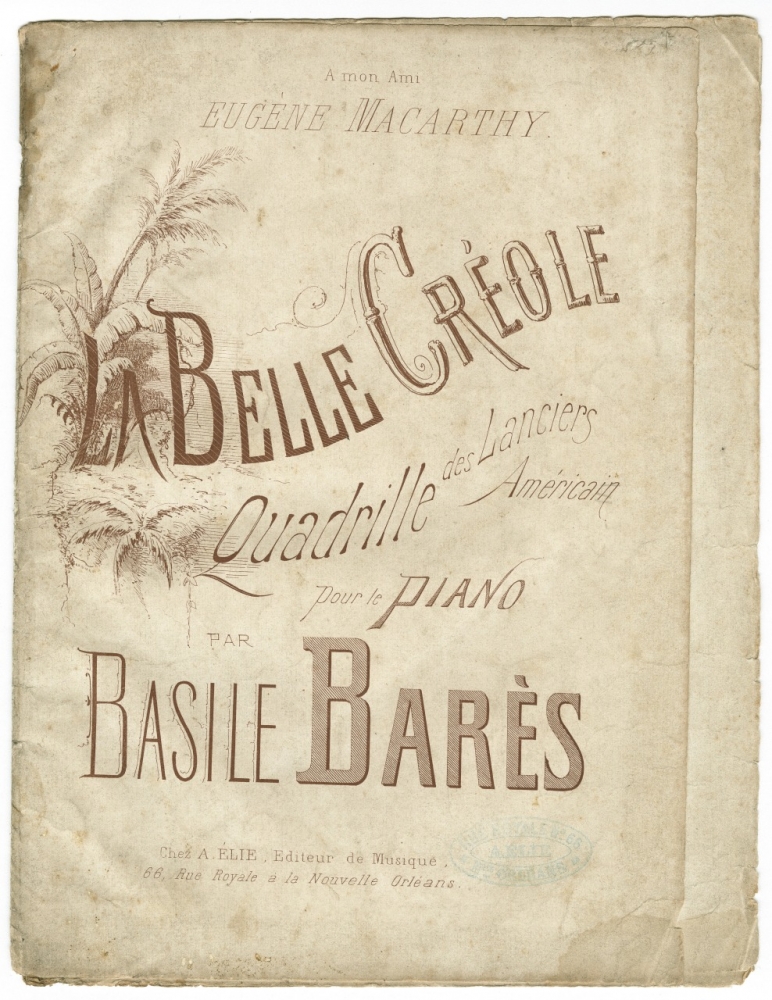

In the early American period, New Orleans emerged as a center for training enslaved Africans in the art of European dance music. Enslaved people were sent from as far as Arkansas to learn to play the pieces their enslavers wished to hear. The city’s close connections with the Caribbean brought already creolized blends of European and African music, as well as the quadrilles and other set dances that accompanied them. These influences would have a lasting effect on American contradance and square dancing, and there are reports of Black musicians and callers playing for audiences of both Black and white dancers from colonial times straight through the 19th century.

“La Belle Créole” is a quadrille composed by African American composer Basile Barès. Barès was enslaved when he published his first compositions, and he became well known after his emancipation. His work in the classical French style shows the impact Black people had on European concert music in the United States. (HNOC, 86-716-RL)

In addition to becoming leading practitioners of European dance music, Black fiddlers of the 18th and 19th centuries were also musical innovators, incorporating African melodies and musical traditions into their playing. Black musicians in the Upper South introduced new ways to use the bow that incorporated African rhythmic traditions and that eventually became a defining feature of Appalachian-style folk playing for both white and Black musicians. The new, distinctly American forms that emerged from this cultural blending would become one of the foundations of country music.

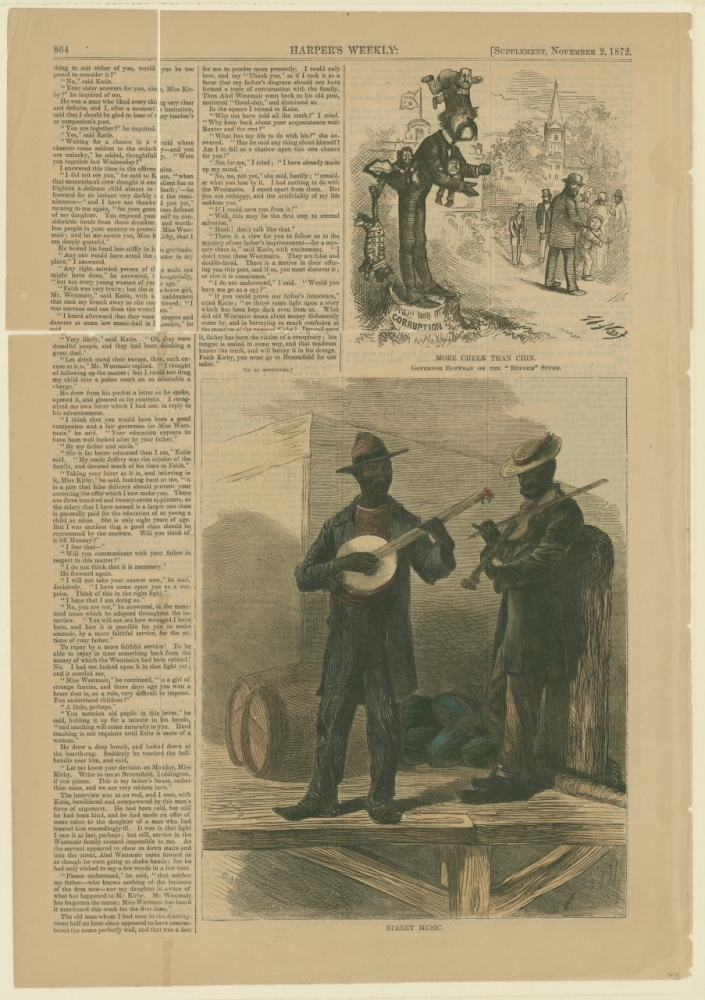

Black musicians also changed how folk music was arranged and performed. As early as 1774, enslaved musicians had combined the fiddle and banjo into a single ensemble. This combination spread throughout the Americas, including the streets and docks of New Orleans. The combo eventually became the foundation for minstrel show bands, and, later, for bluegrass and folk bands.

This 1872 illustration from Harper’s Weekly shows the combination of fiddle and banjo which had become standard by then. (HNOC, 1979.120 i,ii)

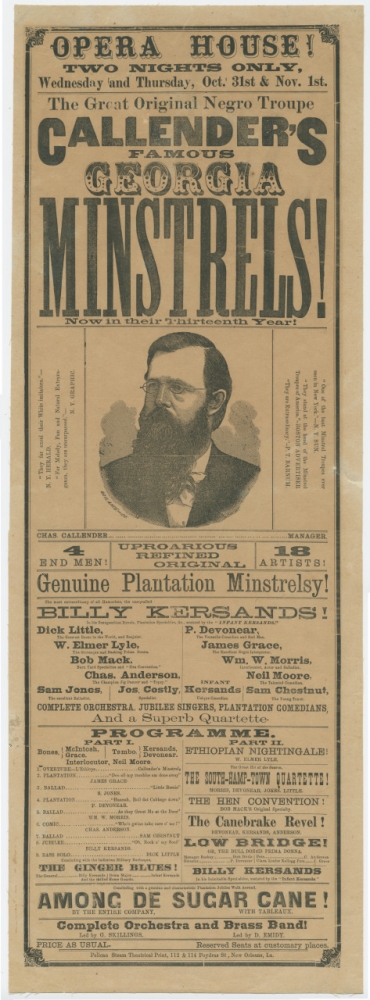

Many of the tunes Black musicians created were appropriated by white musicians during the era of blackface minstrelsy, during the mid- to late 19th century. These songs became popular forms of sheet music, typically published as “Negro jigs” or “Ethiopian melodies.” Whether performed onstage in a racist caricature by white performers in blackface, or in their written form, they were undoubtedly watered-down from their source material. Still, these appearances did much to popularize the Black musicians’ innovations among a broader, and whiter, audience.

This New Orleans newspaper advertisement refers to one of the few Black minstrel troupes of the late 19th century, Callender’s Georgia Minstrels. A review of the troupe’s show in the New York Herald proclaimed that “they far excel their white imitators.” (HNOC, 91-113-RL)

These folk forms set the stage for the recording of the earliest country songs in the 1920s and ’30s. Called “hillbilly” records, this music, released by white performers, was marketed to rural white southerners. (“Race records,” marketed to African Americans, featured Black musicians and genres like blues, jazz, and gospel.) Racially integrated recording sessions were common in “hillbilly” records of the time, and many white stars had Black mentors, collaborators, and influencers. Bill Monroe, the “Father of Bluegrass,” learned from Black blues guitarist Arnold Shultz. The Carter Family, one of the most influential acts in the history of country music, was heavily influenced by Black musician Lesley Riddle. A shotgun accident in his youth claimed two of Riddle’s fingers, leading him to develop a unique style of picking the guitar. Riddle’s influence on Maybelle Carter, to whom he gave guitar lessons, led to her development of the distinctive Carter “scratch” style of playing. Riddle also accompanied Maybelle’s father, A. P. Carter, when he went searching for new songs to record. Riddle helped him gain access to Black spaces such as churches to learn songs that may have never become part of the white country music tradition otherwise. One of the founding members of the radio show that would become the epitome of country music, the Grand Ole Opry, was Black harmonica player DeFord Bailey.

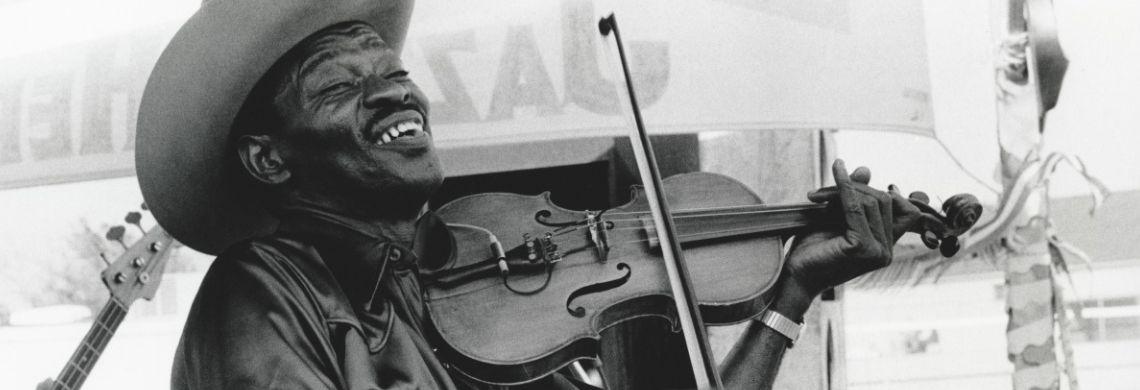

Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown plays fiddle at the New Orleans Jazz Festival in 1976. A virtuosic musician, Gatemouth was known as a bluesman, but he frequently ventured into other folk and country forms as well. (HNOC, 2007.0103.4.668)

As the music industry increasingly sought to market country music along color lines, studios and producers worked to hide the fact that recording sessions were integrated, using white stand-ins in promotional images and advertisements, and pigeonholing Black recording artists into “race records”. Eventually, the pioneering Black musicians of country music were largely forgotten by the public. Still, Black artists continued to contribute to the genre. From national stars like Charley Pride to local favorite (and frequent Jazz Fest performer) Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown, Black musicians proved much more than a footnote in the story of country music. And modern innovators such as Beyoncé continue to show that they will remain so for a long time to come.

About The Historic New Orleans Collection

Founded in 1966, The Historic New Orleans Collection is a museum, research center, and publisher dedicated to the stewardship of the history and culture of New Orleans and the Gulf South. Follow THNOC on Facebook and Instagram.